Horace Andy ‘Midnight Rocker’ Review - Mojo

“This is not only Horace Andy’s best album in 40 years, but it is also a work of lasting power”. Midnight Rocker features producer/musician Gaudi on Stylophone.

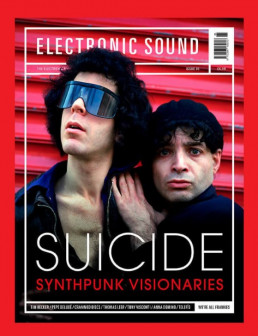

Tony Visconti & Leah Kardos Interview - Electronic Sound Magazine

Bowie producer Tony Visconti and musician-academic Leah Kardos talk about their love of the Stylophone and the making of ‘Stylophonika’, Kingston University Stylophone Orchestra’s debut album.

Vince Clarke: The Idea and The Song

Since 1985 Vince Clarke and vocalist Andy Bell have helmed the group Erasure. Vince also was an original member of Depeche Mode, the music behind the duo Yazoo (or Yaz in the U.S.), remixed many songs for others, plus carried on many collaborations. Photographer Brian T. Silak and I had the distinct honor of meeting with Vince at his Brooklyn, NY, home in 2021 for an interview and photo shoot. Soft spoken, with a razor sharp wit and typical British sense of humor so dry that we almost missed it at turns, Vince gave generously of his time as Brian and I visited his fascinating home recording space. As Brian set up his lighting equipment, Vince played tour guide at The Cabin Studio, and then discussed his career as a founding luminary of synth pop music.

I’ve heard your favorite artist of all time is Paul Simon, yet your music is in a completely different direction. What have you learned from his work?

The reason that I liked Paul Simon, especially in the beginning when I was in my teens, was that I could relate to the songs inasmuch as I could play them on guitar. They weren’t technically difficult. I’m not a very good guitarist. What attracted me to those songs was the simplicity of the arrangements. I think I carried that through with Erasure. We just happen to use more complicated equipment. It’s basically choruses, bridges, and verses.

Thequietus.com published your list of favorite albums. Among your selection were The Human League and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. How were you influenced by the production styles of these early synth bands?

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark is interesting, because the first [self-titled] was a very simple album. It’s very simply produced, and I liked that. The Human League I loved because it’s all about synths and science fiction. I’m not sure what else was on the list. Pink Floyd, probably…

…The Dark Side of the Moon. You had Kraftwerk’s Computer World; David Bowie’s Heroes; Philip Glass’ Glassworks.

Most of the music that I like is song-based. Philip Glass isn’t one of those.

What drew you to his compositions, or to that particular collection of his work?

I think a friend recommended it to me. I started experimenting with doing very repetitive sequences in that style, for B-sides mostly, but using synthesizers instead.

You also mentioned Genesis’ A Trick of the Tail.

I think Pink Floyd’s [The Dark Side Of The Moon] is my favorite album of all time. It still sounds amazing. A Trick of the Tail was the first album that I ever bought. I managed to get enough money to buy a hi-fi stereo system, and I’d never heard stereo before. When I was growing up, radio was mono. This stereo system had two white speakers, and I bought A Trick of the Tail and could not believe the sound of it. I stuck my head between those two speakers – like wearing headphones ??– and listened to it over and over again.

The first single that you bought as a kid was “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us” by Sparks.

Sparks was when I first took an interest in music – not as a musician, but as a music fan. I was playing music, certainly, but I had no intention to become a musician. When Sparks released that single it was on Top of the Pops. It was a big thing in the UK. My mum had bought a radiogram [radio/phonograph player], and I played the record so much that the grooves disappeared.

What made you shift from being a music fan to thinking, “I’d like to make music”?

My moment was when I saw The Graduate. I heard the soundtrack, and I couldn’t believe it. I went out and bought the songbook straightaway and learned all of the songs. They were songs that I could play. Up to that point, I’d watched Top of the Pops and bands like Slade or whoever. The production was so complicated – not something that one thinks they could ever do. I had no idea how they did it. But when I heard these songs from that movie, I bought the songbook. I didn’t sound anything like it – [but] I was close! I thought, “This is what I could do. I could maybe become a musician.” It wasn’t anything mysterious or expensive. I imagined that people would go into these magic studios and come out with these amazing records. Those things were inaccessible to me – but not with Paul Simon.

You came full-circle with Sparks in 1994 when you remixed their song, “When Do I Get to Sing ‘My Way.’” In addition, you’ve worked with Martyn Ware of The Human League and Heaven 17. What has it been like to turn heroes into collaborators?

Well, it doesn’t happen very often, but it’s happened to me a few times. It’s pretty amazing. I remember meeting Sparks, because we met in their hotel and had afternoon tea. They were just… Sparks. You know what I mean? [makes funny facial expression] They were really nice. Martyn Ware produced an album for Erasure [I Say I Say I Say]. That was the first time I got to know him. I spent the whole time while we recorded asking him questions about how he’d gotten a particular sound [with The Human League]. He didn’t remember.

From what I understand, when Andy Bell auditioned as Erasure’s vocalist, you were a hero to him at the time. Was it challenging to become an equal collaborator?

Well, our relationship was quite awkward in the beginning. Not for that reason, but because he was just so shy. He wouldn’t say a word in the studio. Me and the people I was with, the engineer and producer at the time, we would try to make jokes and get him to loosen up a bit – to help him feel at ease. But it took a long time for that to happen. It was the same when we performed live for the first time, because he didn’t move when he was up on stage. He was glued to the mic stand. But once he started moving, he couldn’t stop… [laughs]

You have an amazing home studio here. This, and the previous incarnation that you had in Maine, were both called The Cabin. What are your favorite aspects of working from home? I would imagine it’s been a godsend during this pandemic.

It’s weird. Now that I’m recording nearly everything at home, I miss going to studios. I miss the socialization the most.

Do you bring in an engineer here?

I’m still on my own. It does get lonely, to be honest. Obviously, at this stage of the pandemic, there isn’t much choice. When Andy and I finish a record, we tend to get it mixed outside. Part of that is because I want to get out and meet an engineer and learn something new. I want to hear it in a different room, and get someone else’s perspective on it as well, which is always very important. The last record we did was mixed in London, and we did the vocals in Atlanta [Georgia].

That was The Neon?

Yeah. The record previous to that [World Be Gone] was mixed in L.A. It was nice for me to go to these places and spend a week or ten days working with somebody else. I think I’d go insane if I had to do everything here.

I interviewed Joe Henry [Tape Op #129] a few years ago. He had a home studio which was very integrated into his home life. When you’re working here, are your wife and teenage son around? Do they come down and encourage you?

They’re not interested. My son [Oscar] goes down there occasionally. Now he’s making his own records, so he can take over. I’ll get kicked out, and then he can do his thing. My wife [Tracy Hurley Martin] never goes down there, and I never play her anything.

With the Erasure albums, how much sequencing, writing, and recording is done here versus how much time is spent meeting Andy elsewhere to do vocals or to mix?

Well, the writing is wherever we’re at. He’s got a place in Florida. I’m not going to go down there now, of course. But I might go down to Florida and spend a week. He might come up to New York and spend a week here in the studio. With the last record, we did some writing in London since we were both there. That’s the basic writing. We get the chords together, get the arrangements, and get the melodies. That could be done anywhere we’re at. Then I’ll come back to my studio and start working on the music, and he’ll go away and start working on the lyrics. The last few records, I’ve pretty much recorded all the music downstairs. Andy will find another studio to do his vocals. I’m not really geared up to do the vocals here, nor do I like recording them particularly. It’s too stressful.

You work Logic Pro, but all of your synths continue to be controlled by CV/gate [control voltage/gate synchronization /sequencing], instead of MIDI, which you’ve said you feel is more stable and locks in better.

In the beginning, I didn’t enjoy working with MIDI. It was very convenient, obviously, but I had problems with the timing. Now I’ve got Logic and it doesn’t really matter. Once I record something, it doesn’t matter if I record it via MIDI or using CV/gate. The reason I use CV/gate is because most of the synths here use CV/gate.

They’re older, pre-MIDI synthesizers.

I can’t get [MIDI] retrofits for a lot of them. Now, with the advent of Logic, I’m really into timing. I’m not a “feel” person. [laughs] I like things to be in time.

So, for you, CV/gate provides a more rock-solid feel than MIDI?

It did, initially. Against early MIDI, we could see it. We used scopes and saw the MIDI drifting; but with CV/gate, it would be locked in.

Once MIDI became accessible in the mid-‘80s, was it challenging to continue to work with CV/gate?

Yes. It’s easier [to use MIDI], especially for playing live. It was a godsend, really. I could trigger ten synthesizers on stage. We did a record called Chorus in Hamburg. That was when I went back to using CV/gate sequencers. I decided that for the tour, for that record, I would use live CV/gate sequencers, which was a nightmare from a practical level. It worked really well, but the programming took me forever, working with a [Roland] MC-4 [MicroComposer music sequencer]. Have you ever worked with one? It’s numbers. You put everything in 12s. You dream in 12s. Your CV, your gate, and all the rest. I had all the information on my MIDI sequencer, and I had to get that into the MC-4. The MC-4 only triggers four synthesizers at once, and there was a switching system. There was a way of doing it where two MC-4s could control eight synthesizers, and I could switch from one to the next. The CV/gate in one instance would play on a [Sequential Circuits] Prophet-5 and then it would go over to the [Sequential Circuits] Pro-One or something. I’d program all that. It was all numbers, and it drove me insane. But I’m very nerdy – I wanted to do it.

You were featured in an episode of Rockschool, the ‘80s BBC television program, standing in front of a Fairlight CMI. You were typing on the keyboard, showing how you laid in sequences. You were like a kid in a candy store. Have you found that you have gravitated towards synths over the years because of the programming aspect and the various ways that you can delve into the computer side?

Absolutely. The revolution in electronic music didn’t happen when they invented the [Yamaha] DX7 or the Prophet-5. It happened when they invented the sequencer. It enabled me to program something I could only dream of, which is what I do. I imagine it, and then I make it happen.

Most of your synths don’t have the ability to store patches. How important is the idea of using non-programmable, older synthesizers where you’re creating a new sound each time?

It’s not important. I don’t worry too much about repeating myself, because I know I do it. What’s great about having a synthesizer with no memory is that there are no rules. You can get a big modular system, like a Roland System 700. There’s nothing that I can do on that synthesizer that will break it, unless I start messing about with the power at the back. I don’t know what it’s necessarily going to do. I have an idea of generally how they work, but if I turn a knob here and connect a filter to an envelope, or whatever it might be, or FM two stages together, who knows what’s going to happen? I love that. I love the tactile-ness of it. I spend too much time with a mouse. My son spends too long with his finger on a tablet. [With synthesizers,] I love that two-handedness. Say, for instance, that you’ve got a fairly simple synthesizer like a Pro-One. There are only so many knobs on it. But if you really think about it, it’s infinite sounds. I’ll start with a sound in my head, and then it’ll sound nothing like it, because I don’t know how to get that sound. I’ll think, “Oh, that’ll be a brass part.” I’ll do something and then end up with a sound like an organ.

What have been some of your favorite synths over the years? The Pro-One has appeared on most of the Erasure albums.

It’s been on every one, yeah. I love the Roland [SYSTEM-]100M. I love the [Roland] JUNO-60.

Did you use that on the Yazoo albums?

All of them, actually. That’s pretty much on every album that we’ve ever done. Since then, I bought the [Roland JUNO]-106. My first modular was the Roland 100M. I bought that new as well.

Do you have any suggestions for people who are interested in sound design, sequencing, or song composition using synthesizers?

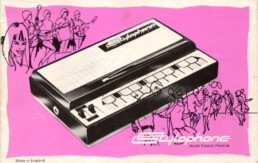

Avoid the presets, that’s for sure. I use soft synthesizers mostly for programming, but also for composition. I’m not precious. If I’ve got an Apple Loop [in GarageBand or Logic Pro] and I can make it sound like something interesting, something that’s unique, then why not? It doesn’t matter what tools you have. It’s about your ideas. Maybe you’ve got a [Dubreq] Stylophone. Just because you haven’t got a Synclavier doesn’t mean you can’t make a great song. That’s the important thing to bear in mind. It’s always about the idea and the song.

You have all of this technology, yet you prefer to write organically on acoustic instruments – at least with Andy Bell for Erasure.

Andy and I have written a lot of records just using guitar or acoustic piano, to see if the song works. If you’re working too hard in the studio on a song, it’s not a really good song.

Is it safe to say that’s the underlying reason why you prefer to keep it simple during the songwriting phase?

It’s one of the reasons. Also, it’s much faster. I can change direction much quicker if I’ve got an acoustic guitar or piano. I’m not worrying about programming bass lines. If I’m playing guitar and Andy says, “Let’s change keys,” I’ll just put a capo on.

Was there a time when your songwriting was more directly tied to technology?

Remixing obviously, because the song is written already. With Depeche Mode, in the very early days the songs that we had were the songs that we played live. I think I only wrote eight songs for that project.

How has the production process for Erasure albums and singles changed over the years from 1986’s Wonderland to 2020’s The Neon?

I think, sadly, it’s gotten more complicated. Everybody says that, but it’s true.

Because of the equipment involved, or because of the logistics of the record label?

It’s my head. It’s quite difficult to come up with a song with just three chords. It’s hard to accept that it’s any good. When I start off and it’s all I can do, I think, “That’s amazing! Bloody hell, that’s right! E, A, and B – That’s incredible!” Then you discover F-sharp minor. Everything’s a discovery. But when you’ve done that for a while, you don’t get those surprises so much.

As it becomes second nature for each generation to have more technology, do you think that leads to some expectation that we need to use that gadgetry all the time?

I don’t feel that. Andy and I did a whole tour with just acoustic instruments, for instance. That was enjoyable. I have no problem not using the technology. I just like to use it – because it’s fun!

Erasure’s The Neon was released in August 2020. What was it like to release a new album during that stage of the pandemic?

Fortunately, we wrote, recorded, and mixed the entire album just before the pandemic. We were in the U.K. mixing at the end of January. I flew back to the States, and I’ve been stuck here ever since. Andy’s got a place in London. He’s married to this guy [Stephen Moss] in Florida, and he hasn’t seen him since the pandemic started. That’s almost two years! Obviously, we did promotions and interviews over Zoom, and that was fine. We had a bit of fun. Andy and I would do these events together, and we probably will continue doing them. He’s a great talker. He won’t stop! We had these “Staying in with Erasure” [live online chats]. It wasn’t about anything in particular. We weren’t promoting anything. It would just be him telling me his troubles. It was really nice. We did a few of those. I think the fans really liked that. Every time we did a new one, Andy’s beard would get bigger and bigger.

You’ve been affiliated with Daniel Miller [Tape Op #110] and Mute Records, from Depeche Mode onward. Has the relationship gone through various phases as your career unfolded?

It’s been the same. Daniel and I are very close. When I first met him, I was 19 and he was 28. In the very beginning, we didn’t know anything about how records were made, or studios; nothing. Then we got to know all that stuff. Over the years, I’ve gotten to know Daniel as a person rather than just the boss. You know that thing about how when someone’s ten years older than you, that ten years gets less and less as time goes by? Now we have an on-the-same- level relationship.

Did you learn a bit from Eric Radcliffe making the Yazoo records? [Upstairs at Eric’s & You and Me Both]

I asked a lot of questions of Eric Radcliffe. I was very interested in the studio and how it worked. He was kind enough to show me. You’re confronted with a thousand buttons – “What does this one do? What does that one do?” I learned a lot from him. I’m sure that I’ve taken techniques from all of the producers and engineers I’ve worked with. I’ve learned tricks, for sure. But I haven’t worked with an engineer and thought, “Let’s rip that off.” It’s more subconscious.

You’ve remixed upwards of 60 songs for other artists, beginning with the Happy Mondays “Wrote for Luck” in 1988. How do you view yourself as a remixer?

The only decisions I make are in the beginning, where I decide whether I want to do it or not. What determines that is whether or not I think I can add something to the track or bring something out in the track that’s not there. I get sent quite a lot of remix requests. I listen to them and think, “That’s perfect. What would you want me for?” When I do a remix, I’m in that group of people who will tend to take the song and strip it down to just the vocal.

What’s Vince Clarke Circuits? You helped design some synth modules: the VCM20, the VCS20, and The Imaginator [VCX-378].

They are all hardware. My younger brother is a genius, and he’s into projects and building devices. I wanted a unit to keep a particular synthesizer in tune that was very difficult to do, so he came up with a piece of hardware that did it. After that, he came up with another piece of hardware, The Imaginator, that was a half-random sequencer. That’s all been done since and before, but this particular sequencer was a songwriting tool. Say you want to write a new bass line, and you’ve got 12 notes to work with. Pick the notes that you want to use for the bass line, and then run it random. It comes up with various patterns, various timings, and if you like one, you can save it and then build [a new song].

So, it’s almost like a song idea generator?

Yes, but most useful for bass lines.

What do you think of electronic pop music and EDM today?

I do like some of it. I made a record with Martin Gore [VCMG] that was a techno- ish, minimalist [instrumental] record, and it got me into listening to [EDM]. I didn’t know anything about it. Then I started doing a little bit of DJ-ing. It hasn’t influenced my songwriting, though.

Over the years, what collaborations have been truest to your personal creative drive and goals?

Erasure’s number one, actually.

Are there any others over the years that have resonated with you at a deeper level?

No. I think Andy Bell is the one. We’ve been together for a long, long time. We have a really great relationship, which is the heart of Erasure. It’s not even the music. It’s actually how he and I get on.

When you come up with a new musical idea, do you tend first to think, “Is this an Erasure song? What would Andy think of this?”

Always.

Once the pandemic lets up, what do you look forward to doing?

Well, I haven’t seen Andy since two years ago. It’s been two years! It’ll be nice to see him in person.

Bren Davies

August 2022

Originally published on tapeop.com

Kingston University Stylophone Orchestra Interview - Electricity Club

The KINGSTON UNIVERSITY STYLOPHONE ORCHESTRA is believed to be the only ensemble of its kind in the world.

From stylus to stardust, the KINGSTON UNIVERSITY STYLOPHONE ORCHESTRA was created by Dr Leah Kardos in early 2019 after producer Tony Visconti, whose studio is based at the University, introduced her to Dubreq, makers of the Stylophone who subsequently donated a collection of new and vintage instruments.

Directed and produced in the majority by Kardos, KUSO’s debut album ‘Stylophonika’ is a fine tribute to the instrument that also explores its strange future possibilities with love and affection, making the most of its component vibrato and glide for a unique collective noise.

Present and past members of the ensemble include Ershad Alamgir, Louis Bartell, Harry Green, Sydney Kaster, George Reid, Cian Ryan-Morgan, Arte Spyropoulou, Estelle Taylor-Noel, Isabella van Elferen, Zuzanna Wężyk, Jess Aslan, Mari Dangerfield, Jack Holland and Billy Wilson.

As well as the original Stylophone series, newer instruments from the Dubreq family like the Gen X-1, Gen R-8 and Beatbox, along with Korg Volca sample sequencers, Theremins, Omnichords, a Moog Grandmother and the human voice feature on ‘Stylophonika’.

Half the album pays homage to electronic music’s pioneers via delightful cover versions of David Bowie, Brian Eno, Wendy Carlos and Jean-Michel Jarre act as entry points while the other half comprises of the original material.

Leah Kardos spoke to ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK about how the KINGSTON UNIVERSITY STYLOPHONE ORCHESTRA took shape and in challenging circumstances, recorded a highly enjoyable debut long player…

Can you remember the first time you heard a Stylophone? I love how some describe it as sounding like “a wasp being cut in half”!

It would have been on the Bowie song ‘Space Oddity’ for sure. I actually didn’t get to play one until I was in my 30s. But I remember being immediately enamoured with the little things. It’s a buzzy sound for sure, but also one that’s capable of stirring emotion.

Hmm… the note names are probably better for music educational purposes.

But the numbers are more immediately accessible for learning, or following along to a known tune quite quickly. As to what might be better for beginners, I guess the system that removes any barriers to access and engagement would be preferable. The instrument is already hugely accessible, being the first ‘pocket’ synth and all. To this day, if you search for synthesisers by price, Stylophones are still the cheapest / easiest around.

As a music academic, how do you feel about some people’s claim that knowledge of music notation and theory is unnecessary?

When it comes to notation, I think it depends on the music and the situation. In some situations notation is not needed – for example, if I was in a band that was improvising, or working in commonly understood structures and forms, or if I was working in electronica with my own sequencing systems, etc. Those of us in the orchestra need it, as we are performing set written arrangements that we perform live together. Knowledge of theory is often intuitively developed, I feel. Theory mostly just explains the reasons why and how certain musical devices work, and we can pick this knowledge up in many different ways – through creating, playing, listening / exposure… and of course by analysing and unpacking it.

How did you come to be introduced to the Stylophone as a modern entity and consider it as a future compositional tool?

It was really by chance. Manufacturer Dubreq got in touch with me, via Tony Visconti, and said they wanted to donate instruments to the university. My first thought when I saw them was: would an ensemble be possible? The limitations of the instruments, in particular, I found really enticing.

Was the orchestra initially for live performance solely? Tuning up must be fun? Is it like a school recorder class?

Tuning up is a necessary ceremony every time we meet, for sure! We use tuning apps on our phones to tune. And of course being analogue synths, the tuning does shift over time, and move about between settings. The upshot is that the group have really become adept at identifying resonance and when something is out of tune slightly.

And, yes, the group was initially about performing live – we only formed in 2019 and that year the goal was to become good enough to play in front of people. We were also developing our sound quite slowly… it was a process of discovery and learning what we could achieve sonically together. We learned a lot together that year! There are some vlogs from our very first few rehearsals on YouTube and we do sound very ropey, much like a school recorder class, yes!

How and when did the idea of recording an album become a realistic proposition, with all the challenges going on?

The album was a way for the group to stay active during lockdown. That’s how the idea started. We met in September 2020 over Zoom and talked about it. I asked the group if they were up for working remotely on such a thing and we all agreed it would be a good project for us to do during the Winter. It was something to keep us busy and distracted during a pretty depressing time.

How did you choose the four cover versions, as each is iconic in its own way?

Some of those tracks were already in our live rotation. ‘An Ending (Ascent)’ was actually the first arrangement we ever worked on and rehearsed, so that had to go in. Similarly we had played ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Blade Runner (End Titles)’ live so those arrangements were ready to go. We discussed the theme for the album and all settled on this idea of ‘classic’ electronica, since we are an orchestra after all. We asked: “What do orchestras do?”, they play standard repertoire. “So what would be standard rep for a synth orchestra?”. That led us to shortlisting Wendy Carlos and Jarre. We also mooted some John Carpenter and Tangerine Dream, but there wasn’t enough room for everything the group wanted to do.

What was it like to work with Tony Visconti on ‘Space Oddity’?

That was a ‘pinch me’ moment; for me at least, since I’m such a Bowie fan. The session was also around the time of the 50th anniversary of the song itself, so that made it feel extra special. He’s quite magical in the studio; anything is possible when he’s around. He also recorded us as a true ensemble, playing together through the Stylophone speakers at the same time (not multitracked or separated out).

We felt like a genuine little orchestra that day. We even recorded some parts for his upcoming album… We became the first (only?) session Stylo orchestra in the world. This was also the first time we sang together in choir mode – which of course opened up a lot of possibilities for us moving forward. It was such a great and inspiring day for us.

On ‘Music For The Funeral Of Queen Mary’ from ‘A Clockwork Orange’, you have the Stylophones sitting with Moogs and they sound wonderfully unsettling?

The combination is fun, I think. We’ve never had Moogs in the orchestra when we’re playing live. But George Reid was a member of the orchestra for the Tony session, and through the remote recording process he came back to us with some amazing Moog takes that we absolutely had to use. He did a brilliant job of treading the line between respectful homage and fresh creativity.

When did you think original compositions would work well within the context of the album? Had this always been part of the concept?

As we were working over the winter of 2020/21, I left space in our schedule for new music. I opened it up to the group – basically saying “If you want to write something for us, I’ll arrange it! Let me know…”; Zuzanna Wężyk responded with ‘Akoustiki’, but no-one else did; students are busy and people had their priorities. So I felt a Harold Budd tribute was appropriate, and I had a Stylophone piece of my own ‘Brundle Beat’ ready to go, so we went with that. I wasn’t sure about including it because a version of it was out on my own 2020 album ‘Bird Rib’, but Gavin at the label Spun Out Of Control was keen on the orchestra version, so it went in at the last minute.

I’m glad we have some original material on the record as it shows the creative and expressive potential of the group. We can face the future as well as looking backwards to the past!

‘Olancha Goodbye’ pays tribute to the late Harold Budd?

eah, it’s inspired by his interlude ‘Olancha Farewell’ (from his 1986 album ‘Lovely Thunder’). I interpolated the theme and built it in a different direction. The gentleness of Budd’s music was something I wanted to try and explore within the brittle Stylophone sounds – could we blend voices with synth tones and create something just as ethereal? That’s where I started with that.

In Visconti Studio we have some beautiful reverbs available, so it was nice to extend and stretch the sound that way. Cian Ryan-Morgan, the Orchestra member who also mixed the project, suggested we re-amplify the sound through the resonant soundboards of the studio’s grand pianos… so we blasted it through them, while one of us held the sustain pedals down. The sound kind of balloons and shimmers through it. Again, it felt fitting for a Budd tribute, since so much of his music is focused on atmospheric piano tones.

What sort of challenges did the Stylophones present in being recorded within a studio environment?

Aside from tuning issues, not many. It was easier to manage with the studio recorded audio than it was to deal with the variously remotely recorded bits and pieces that I was getting from the group. There was lots of Google Drive file swapping going on, and some people were recording with their phones, others with posh set ups. In the end I adopted a ‘more is more’ attitude and threw everything together, often using every version of people’s multiple takes. The results I think are pretty epic; I was so pleased.

Why do you think the charm of the Stylophone still endures?

I think it’s because the instrument survives intact and virtually unchanged since 1968. It sounds retro-futuristic, crude and sweet. There’s something quite vulnerable and a little naïve about the sound. Above all, it’s an instantly recognisable voice, and in the hands of creative musicians can be beautiful and evocative and iconic.

Do you have a particular favourite Stylophone model, whether vintage or modern?

I really like the current ‘all analogue’ version of the instrument. The sound is warmer and rounder than the previous model. Of the vintage units I really adore the 350s – the range and timbral possibilities can’t be beat. It’s definitely the best sounding Stylophone that ever existed… in my humble opinion, anyway.

Will there be a second album? Are there any conceptual ideas you would like to try?

We had no idea how the debut would be received – whether our record would be laughed at or ignored or whatever.

Just in terms of the experience from our end, I know that everyone involved really enjoyed the process of making the record, from planning the track list, checking mixes to getting our photos taken and excitedly discussing ideas about the cover art. I’m sure we will all be keen on doing it again sometime soon. As for a theme, we’d need to discuss it! I’d never want to decide anything without the whole group’s input.

What is next for you? You have book about David Bowie coming out?

Yes, my Bowie book ‘Blackstar Theory’ is coming out around the same time as the ‘Stylophonika’ vinyl, both things I was working on during the lockdown months. It’s all about Bowie’s last works from 2013-2016 – a topic I’ve been obsessed with ever since Bowie passed away in 2016. Other than that, I have a music project with saxophonist Lara James that is all about feminine psychogeography, using field recordings from public places that have been historically unsafe for women. Then, I’m hoping (pandemic willing) that the Stylophone Orchestra can get out and do some gigs in the Spring.

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

30th December 2021

Originally published on electricityclub.co.uk